Asked to curate a show based on the permanent collection of the IUP Museum, I happily explored its vaults. Once I saw the Goya and Kollwitz prints, I knew that my search had ended for I had been deeply moved by their work at different times in my life. How can anyone resist the power of Kollwitz, her insight into human nature and the devastating effects of man’s inhumanity? And Goya: a force so powerful that his works continue to entrance and inspire artists today, almost 200 years after his death. They raised their voices in powerful works that questioned inequities and unfathomable cruelties while maintaining a belief in change for the better. The collection also yielded the work by contemporary artists Herb Olds and Paul Binai who continue the tradition. What attracts me to these works is the undeniable need to address the human condition, to reinforce the positive and to condemn the negative in the societies of their own times. For art is firmly entrenched in its own time, responding to issues and concerns. The contemporary artists I selected join their voices to those of the past by raising questions of life and death, political irresponsibility, personal trials, perseverance, racial and gender inequality, the human spirit, consumer-driven desire, and a belief in a better future. In the heady mix of these sometimes contradictory concerns, these artists maintain an adherence to the highest aesthetic standards, making art that moves the soul and heart with a powerful beauty. This is not a show of doom and gloom, but one that presents belief, humor, and insight in the face of troubling issues and actions that parallel those found in the work of their predecessors Goya and Kollwitz. The invisible threads that connect these artists of different generations define a common ground that defies differences across cultures and eras.

Voices of Concern

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) and Kathe Kollwitz (1867-1945) provide the inspiration for this exhibition. Their work, including restrikes of some of their prints in the collection of the IUP museum, speaks not only about man’s inhumanity to man but also of the consequences of such actions. Known for their incisive and moving critiques, these two artists became the social consciences of their times. Goya turned his back on his job as a painter at the Spanish court to concentrate on dark works that illustrated “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance or self-interest have made usual,” as he wrote about his 80-print series “Los Caprichos” published in 1799. It included The Sleep of Reason which “produces monsters,” and unleashed Goya’s unbridled imagination. His fantastical monsters have captivated audiences and inspired artists to speak of injustices in their own times.

About 100 years later, Kollwitz turned her attention to the plight of peasant workers in her print series The Weavers and Peasant War, both inspired by contemporary plays. She lived through the two world wars in Germany and lost her son in the fighting. These personal experiences sharpened her compassion for those who suffered, and she brought their anguish and misery to the page in simple and direct drawings. Even at the moment of the greatest loss, Kollwitz inserted an intense and moving sense of hope, revealing that we are rarely totally alone and that others can help alleviate the most horrific emotions.

It is that humanity that I believe exists in the personalities and work of Kollwitz and Goya who both dared to breach decorum by confronting injustice in their art. They refused to remain silent, and they believed in art’s innate ability to address difficult issues. That is what links these two to this exhibition’s artists who turn their talents to face today’s troubling times. Here is the common ground between past and present, connected with invisible threads.

Dangerous Beauty

© vicky a clark 2010

Critic Dave Hickey coined the phrase “dangerous beauty” in the 1990s to point out a delicious paradox in art of all ages, suggesting that art can be aesthetically pleasing and challenging or confrontational simultaneously and that the beautiful can be subversive and the dangerous tantalizing. Just like dangerous femme fatales and black widows, art can seduce the viewer into unexpected realms. Beauty is one way to increase accessibility. Goya’s monsters and Kollwitz’s compassion draw in the viewer, and the artists in this show follow in their footsteps by finding effective ways to address serious issues in their art.

The immediately obvious connection between the historical and the contemporary artists is their use of the human figure. Paul Binai focuses on the darker side of the individual with his bold and brightly colored figures set into a rigorously painted field. His drinker, part of the museum collection, fills the entire canvas yet appears alienated and isolated. He also looks rather ominous with his animal-like features, which match the intensity in some of Goya’s monsters.

Herb Olds’ carefully rendered figures, also from the museum’s collection, are imbued with a humanity. They project compassion, paralleling the psychological insight revealed in the subjects of Kollwitz and Rembrandt and even the figures from Giotto’s Arena Chapel. You feel that you can see into the souls of these humans and through them into the minds of these artists who are separated by centuries but connected by a common understanding of the human condition.

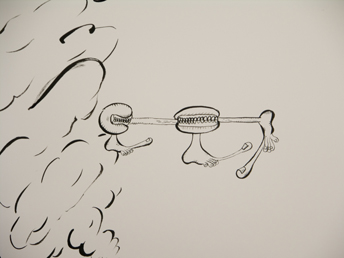

Barbara Weissberger is the one artist in the exhibition who acknowledges that she was inspired by the work of Goya. Her grotesques resemble some of Goya’s creatures, and her work is equally satirical. These hairy creatures with large choppers, perhaps relatives of cousin Itt from the Adams family, are icons of consumerism. Combining sources from high art and popular culture to critique materialism and desire, Weissberger places animated body parts, from feet with overextended big toes to long and winding intestines, under the eye of surveillance cameras. The title of a recent show at Hallwalls—Are we just to stand and watch this?—describes this earlier body of work as well.

The complexity of human nature is investigated by several artists. The large-scale, sculptural silhouettes of Adrienne Heinrich seem to glow from within, giving a sense of warmth and even shelter comparable to the compassion in the work of Kollwitz. Whereas Goya let out the monsters, Heinrich looks to the internal by embedding a range of found objects (feathers, dolls. etc) to hint at multi-faceted identity. Essentially anonymous individuals, these totems project understanding and strength when grouped together.

Jennifer Howison starts with a similar, generic silhouette which she decorates to create distinct personalities. Her tiny, hand painted dolls become larger-than-life stars in mini-narratives which speak of love, isolation, pain, and other aspects of human nature. Photographed in evocative settings, her poignant characters reveal the connects and disconnects in life. They seem so recognizable, as if personal friends or actors from television and the movies, yet at the same time they, like the figures of Heinrich, remind me of Giacometti sculptures, exhibiting an intensity born of troubling times.

These direct evocations of the human body are based on personal experience that results in a myriad of disparate associations as the viewer recognizes parts of themselves or their own experience. They become, in a way, universal figures, sharing connections through those invisible threads. Timothy Hadfield and Susanne Slavick, on the other hand, have been inspired by specific situations. Hadfield’s miniature portraits float on large pieces of white paper which encourages an intimate viewing, more in line with the private nature of the prints of Goya and Kollwitz. Studying the exquisitely drawn faces reveals common features, but in fact, each man is incarcerated on death row. Hadfield unsettles us by forcing us face to face with criminals on a personal level while simultaneously informing us about the abnormal preponderance of black males in this population.

While Hadfield refers obliquely to death, Mary Mazziotti dares to touch the unthinkable by inserting the medieval dance of death into collectible textiles of the 20th century. Death comes directly into our lives in the form of dancing skeletons, reminiscent as well of Mexico’s day of the dead celebrations. Her memento mori representations infiltrate our living spaces not only as works of art but as useable pillows, aprons, and tablecloths. Combining cartoon-like and stereotypical images, she makes death into an everyday character who cannot be denied.

In a way, Susanne Slavick addresses the question of inevitability by appropriating black and white photographs from the Internet of war torn areas of the world. Into these journalistic images of specific situations, she hand paints renewal and restoration with culturally appropriate motifs. As if mending a tear, she reclaims cultural potential and potency for areas of desolation with her small and quiet gestures as if to suggest that the individual can affect change one step at a time. She rarely chooses images with humans, but their very absence reminds us of the displaced and the dead. Slavick complements that loss with hope and a sense of history, refusing to dwell only on the unthinkable.

Delanie Jenkins brings concern and hope to her body-oriented work as well. Her sculptures based on clementines, inspired by despair about the impending war in Iraq, concentrate on the skin of the fruit as a surrogate for human skin, that thin membrane which is our most immediate connection with the world. The pitted and scared surfaces have been reconstituted into spheres that somehow look like beach balls, adding a sense of play. The possibility of action becomes concrete in her continuing performance piece where she counts the number of strands in a shorn ponytail. Her repeated actions constitute a type of meditation or even an out-of-body experience.

This repeated process reminds me that when reading about abstract artists in postwar Germany, I was moved by the idea that amidst all the destruction and despair, just making a gesture, a mark on a canvas, was an act of faith in the future. It was also, I believe, a hope that art could make a difference. This faith and belief as well as the art it produces continues to move me and explains why I have put the work of these artists together: to show that art is a powerful way to voice concerns and a tool to make sense of chaos and confusion while never losing its magical presence.

Installation view featuring sculptures by Delanie Jenkins

Paul Binai

Herb Olds

Barbara Weissberger

Adrienne Heinrich

Jennifer Howison

Timothy Hadfield

Mary Mazziotti

Susanne Slavick

Francisco Goya

Kathe Kollwitz