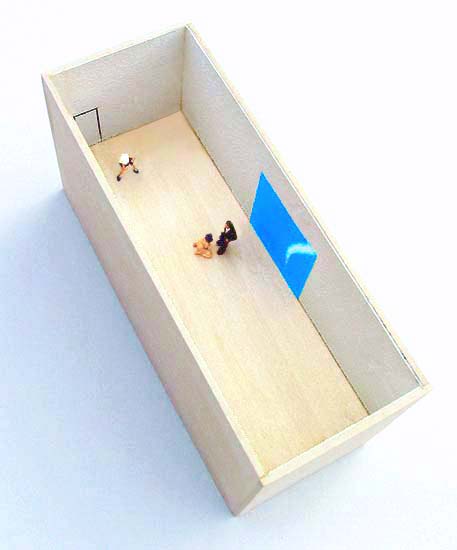

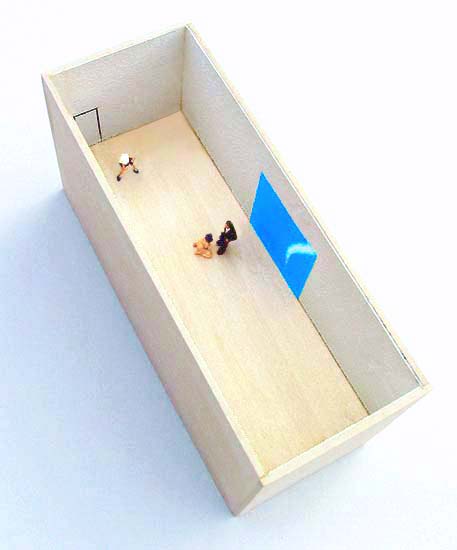

shows i never got to do

2007

Wood, Acrylic Paint, HO Scale Figures

3" x 6 3/16" x 2 5/16"

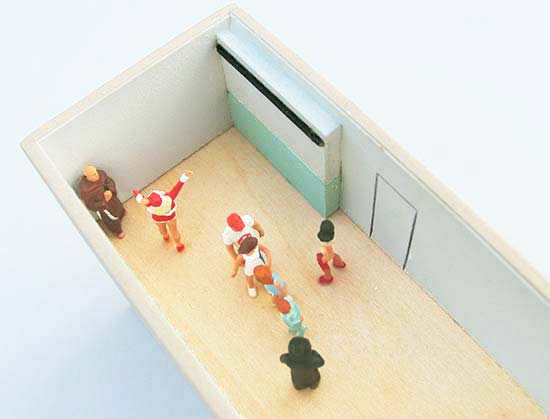

2005

Wood, Acrylic Paint, HO Scale Figures

3" x 4 3/16" x 1 15/16"

Bill Radawec ∞The Man Behind the Curtain

An old-fashioned storyteller transported to the dysfunctional now, with a little bit of magic

realism and absurdist theater thrown in, Bill Radawec feeds on information like most gobble McDonalds. For instance, did you know that Frank Lloyd Wright's original middle name was Lincoln and that his son invented LincolnLogs after being fired by his father? Bill did, and hemade a work of art about it. Did you know that Frank Lloyd Wright designed the dinnerwarefor the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo which was demolished in 1968, the same year that the Beatles released the White Album? Bill did, and he made a work of art about that too, in a white-on-white work, linking the two unrelated events that occurred in the same tumultuous year. He connects the dots as he spins yarns like no other, a skill clearly evident in his boxes containing"his" little people.

Everyone loves a good tale, and everyone loves the dioramas in the natural history museum.

Radawec combines the two in small tableaux that encourage intimacy, close looking, an uncomfortable yet enticing form of voyeurism, and above all, curiosity. In fact, Bill is like the

wizard of Oz, a contemporary behind the scenes/behind the curtain mastermind who orchestrates scenarios for his little people who are inspired by/connected to, of course, the munchkins. But he is equally comparable to Scheherazade, the master storyteller (mistress/storyteller?). In person, he talks non-stop, regaling visitors with stories that hinge on sometimes bizarre connections, our "six degrees of separation." In a recent conversation, for example, he wondered why we eat beef and not cow, pork and not pig while we do eat chicken and lamb. That's how the mind of Mr. Bill works.

I would love to see a PET scan of his brain; I bet it would light up with multi-colored synapses

firing rapidly and constantly in complex patterns. And then he could add names to each color, referencing the made-up names for house paint just as he did for a series of works where he

strung together those weird names to create enigmatic short stories. He recognizes our fascination with synchronicity and serendipity, currently reveling in them in little worlds

composed with little people placed in little boxes. Just to make it interesting, he installs these pieces across a wall at different heights, making some scenes visible, others invisible, and some

awkward to view, making us work to be voyeurs. We could just look at the entire wall as a study in abstraction, a series of Judd-like boxes arranged according to aesthetic conventions, but once we glimpse one tableau, it is impossible not to look at each and every one of them, studying them as we do the complex boxes of Joseph Cornell. Radawec inserts the personal

into the impersonality of minimalism.

Bill constructs a diorama-like world with the little people encased (trapped? contained?

presented? preserved?) in a small box. Who knows what brought his characters to this

particular moment, and who knows what will happen next? For like the childhood games, snap the whip/statue, these figures are frozen at an arbitrary moment in time, just like the preserved

animals in natural history museum dioramas. Think of the story told with the lions in the diorama at the American Museum of Natural History, where the father goes out to get food for

his family, a lovely analogy to the American family. Ah, but what a fiction that turned out to be, as revealed by Donna Haraway in her fabulous article "Teddy Bear Patriarchy." For in the

real world—whatever that means—the mother lion is the killer while the father lion relaxes, secure in the knowledge that his mate will provide what the family needs. But I am already on

one of my own tangents; I just can't help myself when thinking about Bill and his work. In my defense, there is a connection; Bill's stories mix fact and fiction just as the dioramas do.

There are so many things to consider about Bill's work. Many are postmodern queries— what

is reality and whose reality is it? what is the relationship between fact and fiction? what's

public and what's private? —layered in the work though they never impose themselves arbitrarily or dominate because Bill's little people are themselves a demanding lot.

The connection to The Wizard of Oz is part of the backstory of this body of work. When living

in Los Angeles, Bill became fascinated with the Culver Hotel, the site of munchkin shenanigans

during filming. Stories of their supposed debauched behavior in the hotel were widely circulated, supposedly by an adult Judy Garland, even though several participants have refuted

their veracity, which did not prevent them being retold in the 1981 film Under the Rainbow. Did the munchkins really trash the hotel because they feared they would not be paid? Were

they swinging from the chandeliers? Did a little person need to be rescued after falling into a toilet? Who cares? The stories have become part of the lore, part of our fascination with the

lives of little people, evidenced currently by yet another reality tv show. Their stories are exactly the kind of fact/fiction inversion that fascinates Bill.

Adding to the popular culture backdrop is a more personal source. The basement of Bill's

childhood home in Parma, Ohio, was flooded, destroying many of his childhood possessions. He began to recreate that claustrophobic space complete with the watermarks left by the flood in

room-sized installations, just as he painstakingly recreated the cracks left in his LA residence after an earthquake in minimalist drawings. This personal mapping references systems and

autobiography, actualizing the obsessions of both. Soon he began to make small models of his memory-laden space and decided to populate them with figures in order to give a sense of scale.

And then the work exploded.

© vicky a clark 2010

Bill's little people are actually HO train figures, readily available in catalogues for model train

buffs. The range and variety of these figures is absolutely amazing, which naturally caught Bill's attention leading him to move beyond using them just for scale. There is the tableau

where a naked woman is on her knees before a man who holds a gun to her head while another woman flashes her boobs, performed before a miniature reproduction of one of Radawec's

contrail paintings, which reference the gestures marking the perfect skies on 9/11. There are others where a variety of characters seem to be waiting, for what we don't know. The peep-

show aspects are enhanced by his discovery of odd figures that don't seem to belong to a model train buff's repertoire, figures that seem to be lifted from mass media accounts and

images of unsavory activities. Still there is also a sweetness and sadness about them, especially in their miniaturization. As Bill has said, "while some of the 'little' people are having fun in

the basement models, they're also getting caught in the act."

These narratives with their curious connections take us on a wondrously fanciful journey, comparable, I believe, to stories by South and Latin American magic realist writers or the plays of the absurdist group. Radawec is grounded in the now where information dissemination has become an overwhelming deluge that we struggle to sort, organize, and understand. We no longer can be assured of accuracy, and we no longer believe in universal truths as we have become skeptics par excellence. We are, to borrow a phrase from one of my favorite authors A.S. Byatt, 'theoretically knowing." Yet we remain naïve as we continue trying to understand the world and our place in it. Some do this by a process of simplification while others, like Bill, add layers to a point of excess.

This is obvious in the small worlds created by Radawec—am I the only one hearing the Disney

tune "It's a small world," in the background? He does not give us concreteness; instead he

gives us a fragment, a figment of his imagination. As history has become more than just facts and stats, as we insert anecdotal material like journals and diaries, Bill presents us with similar

moments as contemporary parallels to characters from Moliere and/or comic books. In an absurdist way that still tugs at our heartstrings, Bill's "cockeyed history" lessons reveal more

than we could ever imagine as truth is stranger than fiction and fiction is strange enough itself.